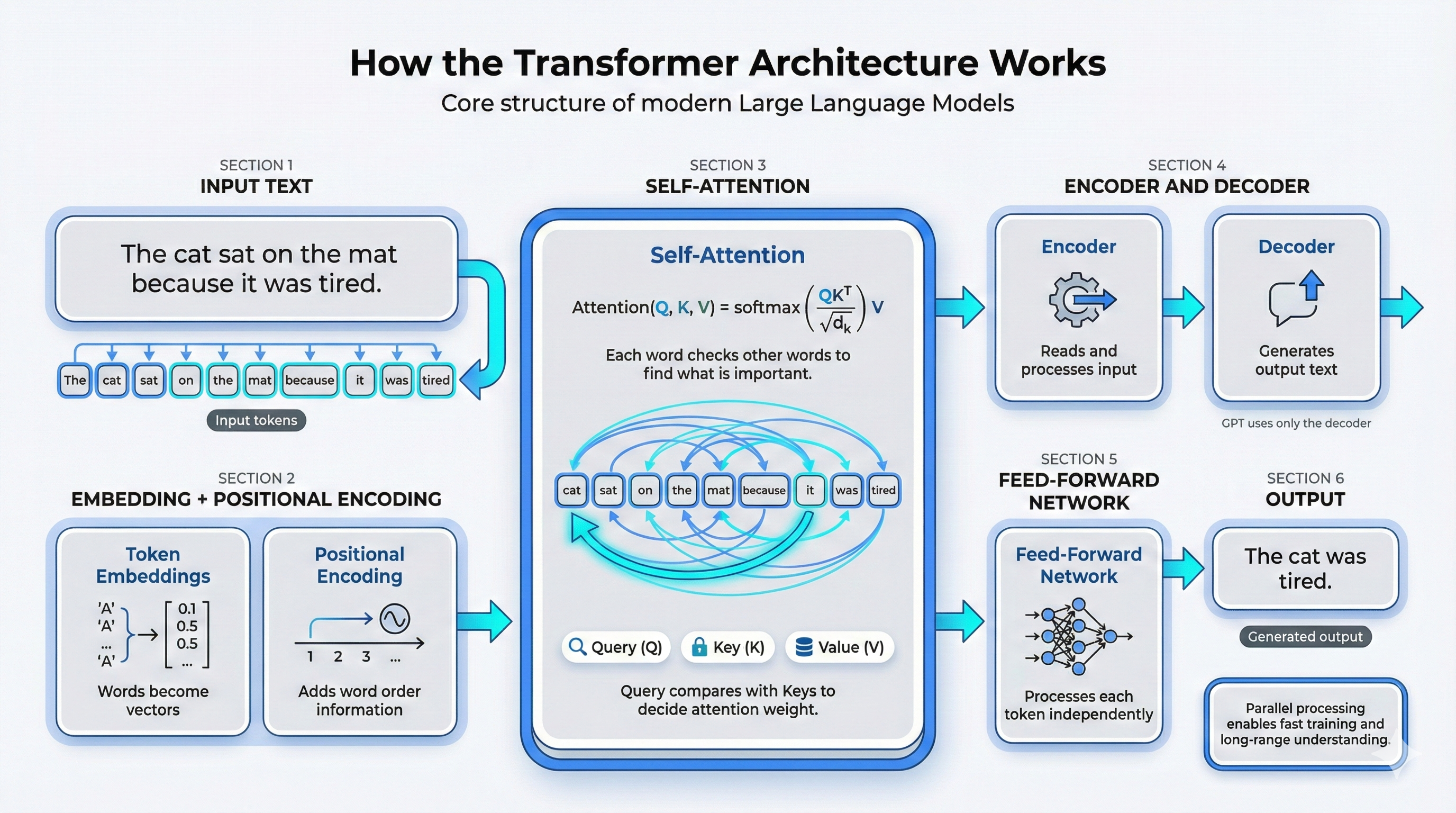

1. Fundamental Architecture: The Transformer

The foundation of modern LLMs (Large Language Models) is the Transformer architecture [1].

Unlike RNNs (Recurrent Neural Networks) and LSTMs (Long Short-Term Memory networks), which process text one step after another, the Transformer processes the entire sequence in parallel. This allows better modeling of long-range dependencies and faster training [1].

Figure: Flow of the Transformer architecture (attention, encoder/decoder, feed-forward). Source: Vaswani et al. [1].

How it works in simple terms. The diagram above shows the path the data follows:

- The input text is turned into vectors (embeddings).

- Those vectors enter a stack of layers. In each layer, three things happen in order:

- Self-attention: looks at all the tokens together and decides how much each word should “attend to” the others, so the model captures relationships in the sentence.

- Encoder (if present) or decoder: processes this attended representation.

- Feed-forward: refines each token position on its own.

- The output of one layer becomes the input of the next.

- After several such layers, the model has a rich representation of the whole sequence and uses it to predict the next token.

In short: input → attention (who relates to whom) → encoder/decoder → feed-forward → repeat over layers → final representation for prediction.

Main components:

Self-attention mechanism. Self-attention is the core of the Transformer [1]. It lets the model assign different importance weights to words in a sequence when making predictions. For example, in “The cat sat on the mat because it was tired,” the model can learn that “it” refers to “the cat.” In mathematical form, attention is:

Attention(Q, K, V) = softmax(QKᵀ / √d_k) V

A more detailed mathematical explanation is given in [2].

Encoder and decoder. The original Transformer has both encoder and decoder stacks [1]. The encoder processes the input; the decoder produces the output. Many generative models, such as GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer), use only the decoder [3].

Feed-forward networks. After the attention block, each token is processed by a position-wise fully connected feed-forward network [1].

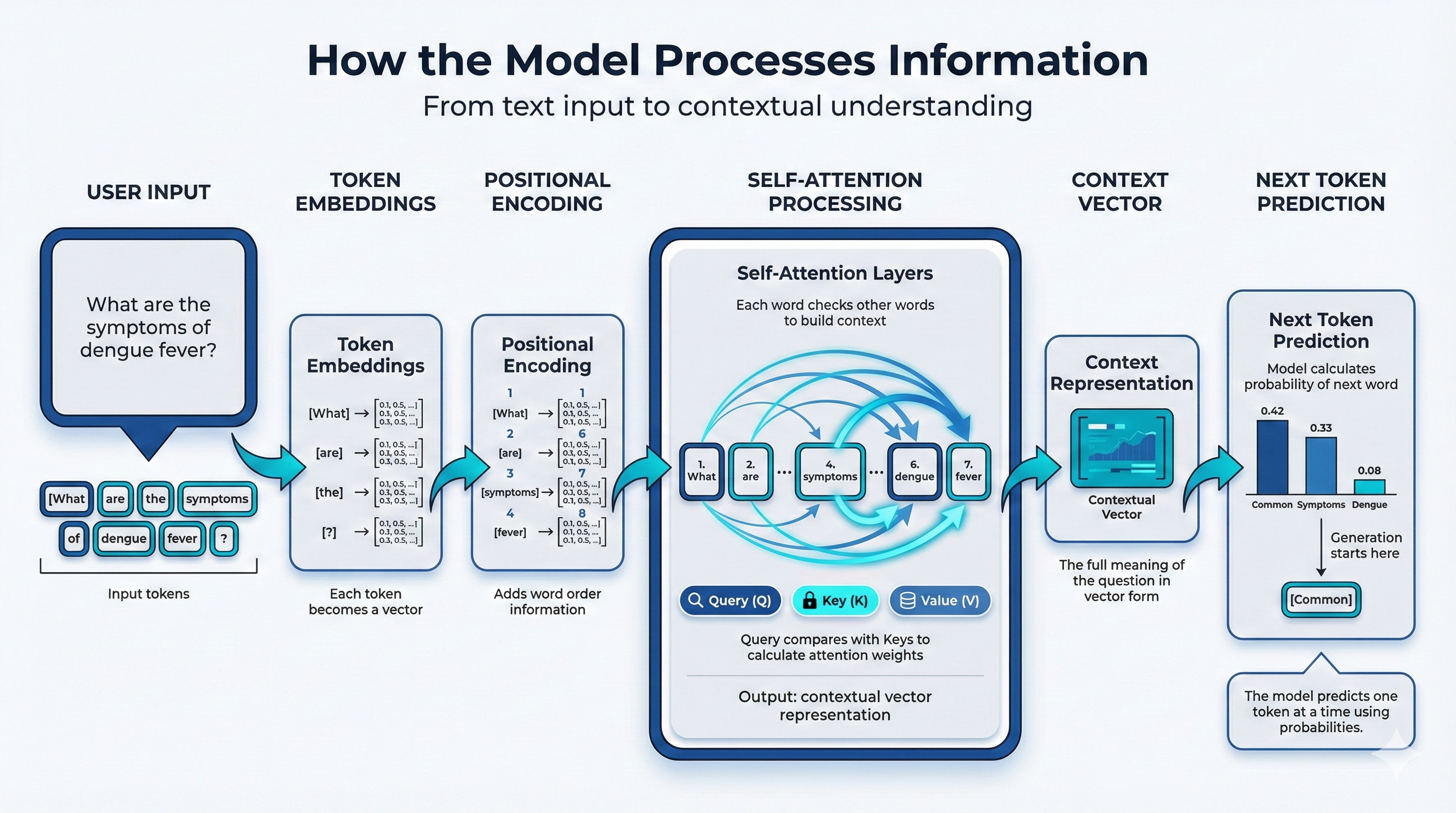

2. How the Model Processes Information

Before the model can compute anything, text must be turned into numbers.

Figure: From user input to next-token prediction (tokens, embeddings, positional encoding, self-attention, context vector).

How it works in simple terms. The diagram above shows the path from the user’s question to the first word of the answer:

- User input. The user types a question (e.g. “What are the symptoms of dengue fever?”). The text is split into input tokens: each word or punctuation becomes a token, e.g. [What] [are] [the] [symptoms] [of] [dengue] [fever] [?].

- Token embeddings. Each token is turned into a list of numbers (a vector). For example [What] becomes a vector like [0.1, 0.5, …]. This is the step where words become a form the model can process [1].

- Positional encoding. The model needs to know the order of the words. Positional encoding adds numbers that tell the model that “What” is the 1st word, “are” is the 2nd, and so on. So the model knows that “dengue fever” and “symptoms” are related in the right order [1].

- Self-attention. Inside the self-attention layers, each token “looks at” the others to see how they relate. For this question, “symptoms” pays more attention to “dengue” and “fever” than to “what” or “are.” The model uses Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V) to decide how much attention each word gives to the others. The result is a contextual vector representation: one representation that encodes the meaning of the whole question [1].

- Context vector. The output of attention is a single high-dimensional vector that holds the model’s “understanding” of the question. This is the context representation used for the next step.

- Next token prediction. With the full context, the model predicts the next token. It assigns probabilities to many possible next words (e.g. high for [Common], [Symptoms], lower for others) and then picks one (e.g. [Common]) according to its sampling strategy. This is where the answer starts. The model always generates one token at a time [1].

Embeddings. Tokens are converted into high-dimensional vectors. In this space, words with similar meanings sit closer together [1].

Positional encoding. The Transformer does not process tokens in order. So it needs extra information about the position of each token. Positional encodings add that order information [1].

Queries, keys, and values (Q, K, V). For each token, the model builds three vectors: Query, Key, and Value [1]. The Query of one token is compared to the Keys of other tokens to get attention weights. The Values are then combined using these weights. This is how the model learns relationships between words.

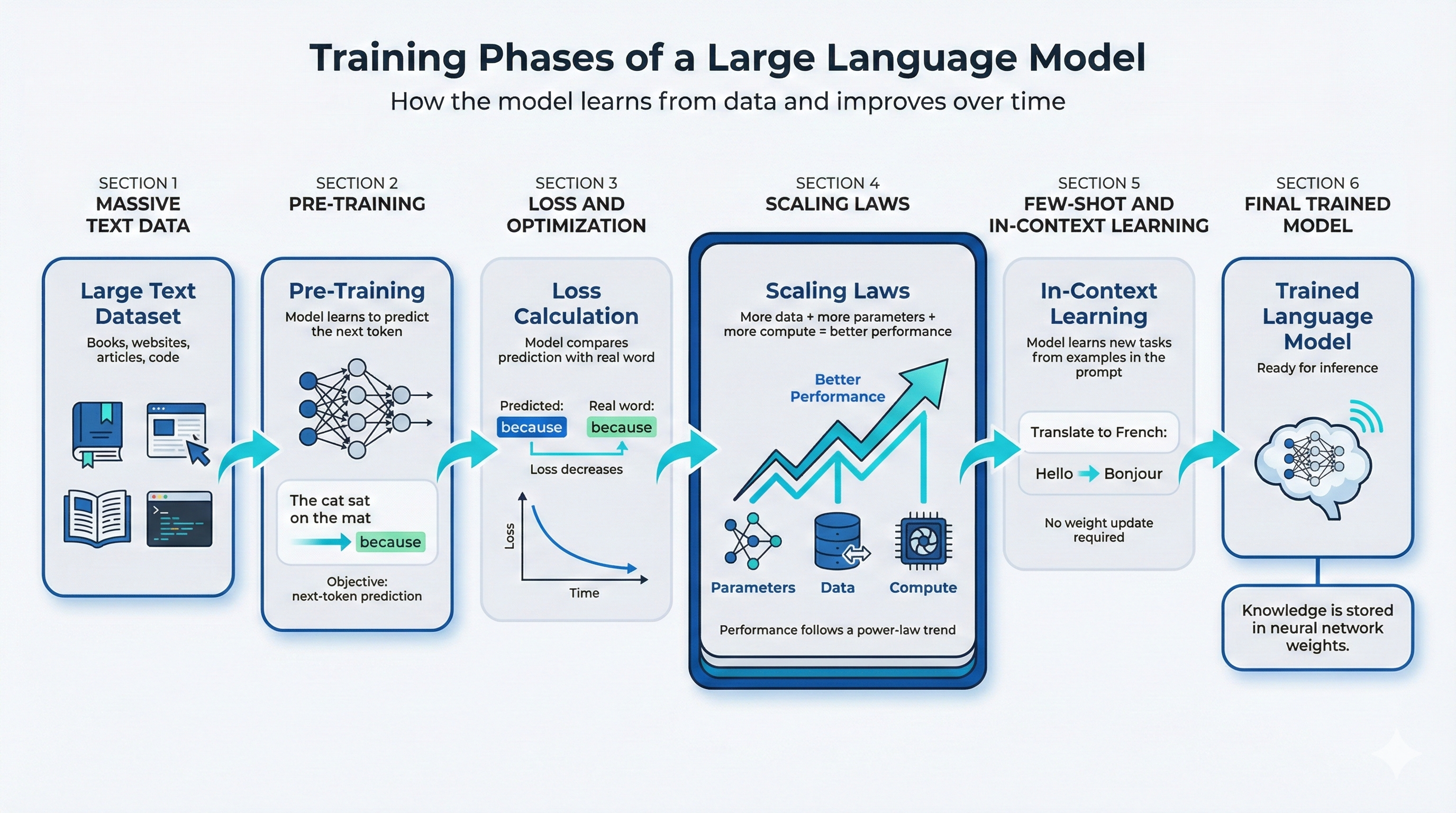

3. Training Phases

Training turns a generic model into one that can predict text well. It happens in several phases.

Pre-training. Large language models are trained on very large text corpora using next-token prediction [3]. The goal is to model the probability of the sequence:

P(x) = ∏ P(x_t | x_<t)

So the model learns to predict each token given all previous tokens. From this, it learns grammar, structure, and factual associations. The training loss is usually cross-entropy.

Figure: Training phases from data to a trained model (dataset, pre-training, loss, scaling laws, in-context learning).

How it works in simple terms. The diagram above shows how the model learns from data and gets better over time:

- Large text dataset. Training starts with a huge amount of text: books, websites, articles, and code. This is the raw material the model will learn from [3].

- Pre-training. The model is trained to predict the next token. For example, given “The cat sat on the mat”, it learns to predict a likely next word (e.g. “because” or “and”). By doing this over and over on billions of tokens, it learns grammar, facts, and how words relate [3].

- Loss calculation. For each prediction, the model compares what it predicted with the real next word. When the prediction is wrong, a loss (error) is computed. The training process updates the model so that this loss decreases over time. The graph of loss vs. time goes down as the model improves [3].

- Scaling laws. Performance improves in a predictable way when we add more data, more parameters (bigger model), and more compute (more computing power). This follows a power-law trend: better performance comes from scaling these three factors [4].

- In-context learning. After pre-training, the model can learn new tasks from examples in the prompt without changing its weights. For instance, if you show “Translate to French: Hello → Bonjour”, the model can do more translations. No extra training step is required; the ability emerges from scale [3].

- Trained language model. At the end, the model is ready for inference. All the knowledge it learned is stored in the neural network weights. When a user asks a question, the model uses these weights to generate answers [3].

Scaling laws. Model performance improves in a predictable way when we increase parameters, dataset size, and compute [4]. This follows a power-law relationship. Recent work also studies what happens when data growth is limited (data-constrained regimes) [5].

Few-shot and in-context learning. Large models such as GPT-3 can do few-shot and zero-shot learning without updating their weights [3]. By putting examples or instructions in the prompt, the model solves new tasks. This ability emerges from scale and training, not from extra task-specific fine-tuning.

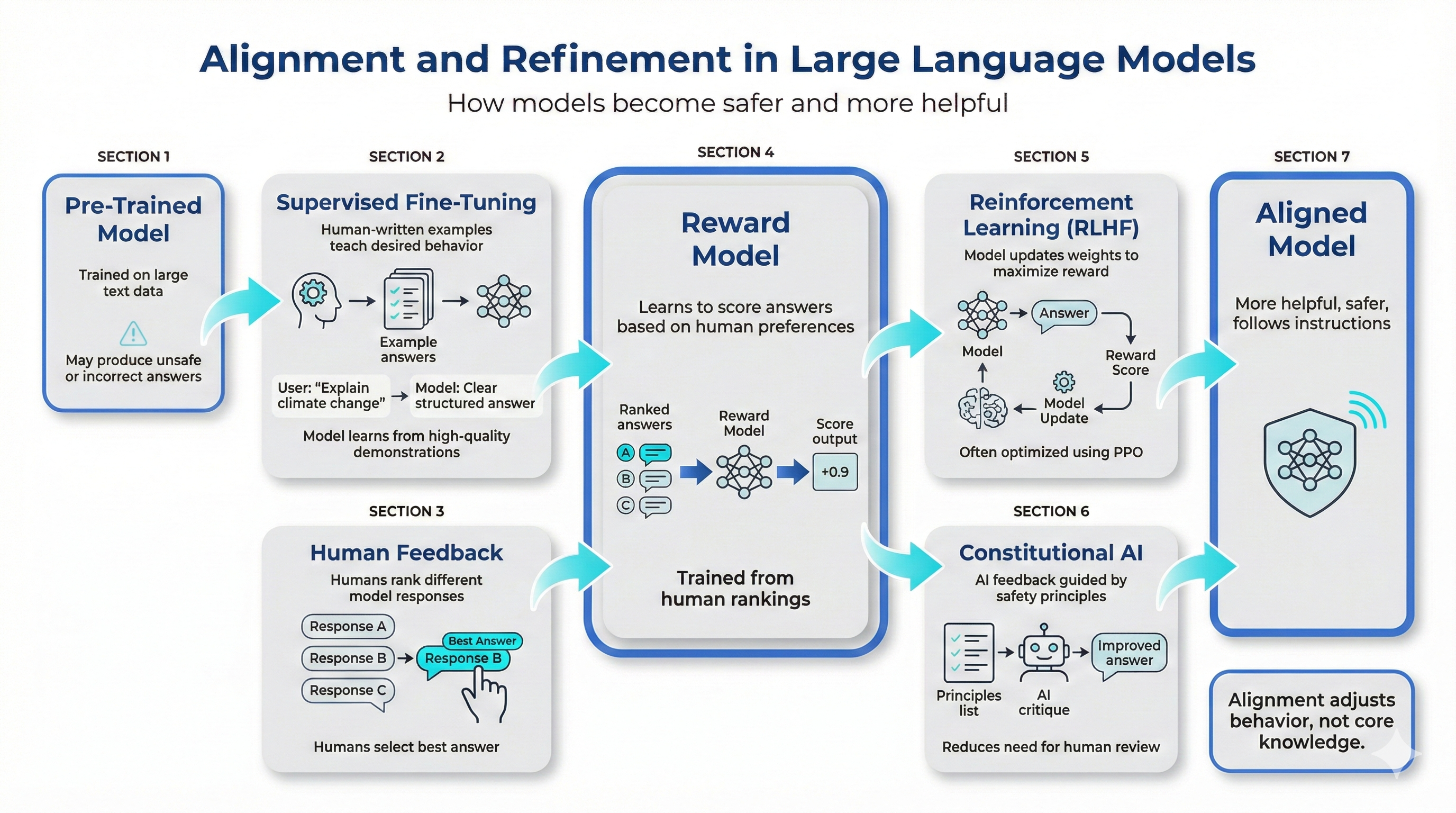

4. Alignment and Refinement

Raw pre-trained models can produce unsafe or unhelpful outputs. Alignment techniques are used to improve behavior.

Figure: How models become safer and more helpful (human feedback, reward model, reinforcement learning).

How it works in simple terms. The diagram above shows the main steps of alignment:

- From the raw model to answers. The pre-trained model generates several answers to the same question. These answers are the starting point for human feedback [6].

- Human feedback. People (annotators) read the model’s answers and rank them: for example, answer A is better than B, B is better than C. These ranked answers show what humans prefer: more helpful, safer, or more accurate responses [6].

- Reward Model. A separate model, the Reward Model, is trained on these human rankings. It learns to score each answer with a number (e.g. +0.9 for a good answer, lower for worse ones). So “human preferences” are turned into a score the computer can use. This model is trained from human rankings only; it does not generate text [6].

- Reinforcement learning (RLHF). The main LLM is then trained with reinforcement learning (often PPO, Proximal Policy Optimization) to maximize the score given by the Reward Model. When the LLM produces a good answer, the reward is high; when it produces a bad one, the reward is low. Over time, the LLM becomes more helpful and aligned with what humans want [6].

- Aligned model. After this process, the model is refined: it is more likely to give safe, useful answers and less likely to give harmful or unhelpful ones. Alignment does not change what the model “knows” from pre-training; it changes how it behaves when it answers [6].

SFT (Supervised Fine-Tuning). The model is fine-tuned on high-quality human-written examples that show the desired behavior [6].

RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback). The process in [6] works as follows. Human annotators rank model outputs. A Reward Model is trained from these rankings. Then reinforcement learning (typically PPO, Proximal Policy Optimization) is used to train the LLM to maximize that reward. This makes the model more helpful and aligned with user expectations.

Constitutional AI (RLAIF). Constitutional AI replaces part of human feedback with AI-generated feedback guided by explicit principles (a “constitution”) [7]. The model critiques and improves its own outputs using these rules. This is Reinforcement Learning from AI Feedback (RLAIF). It allows scalable alignment with less human supervision.

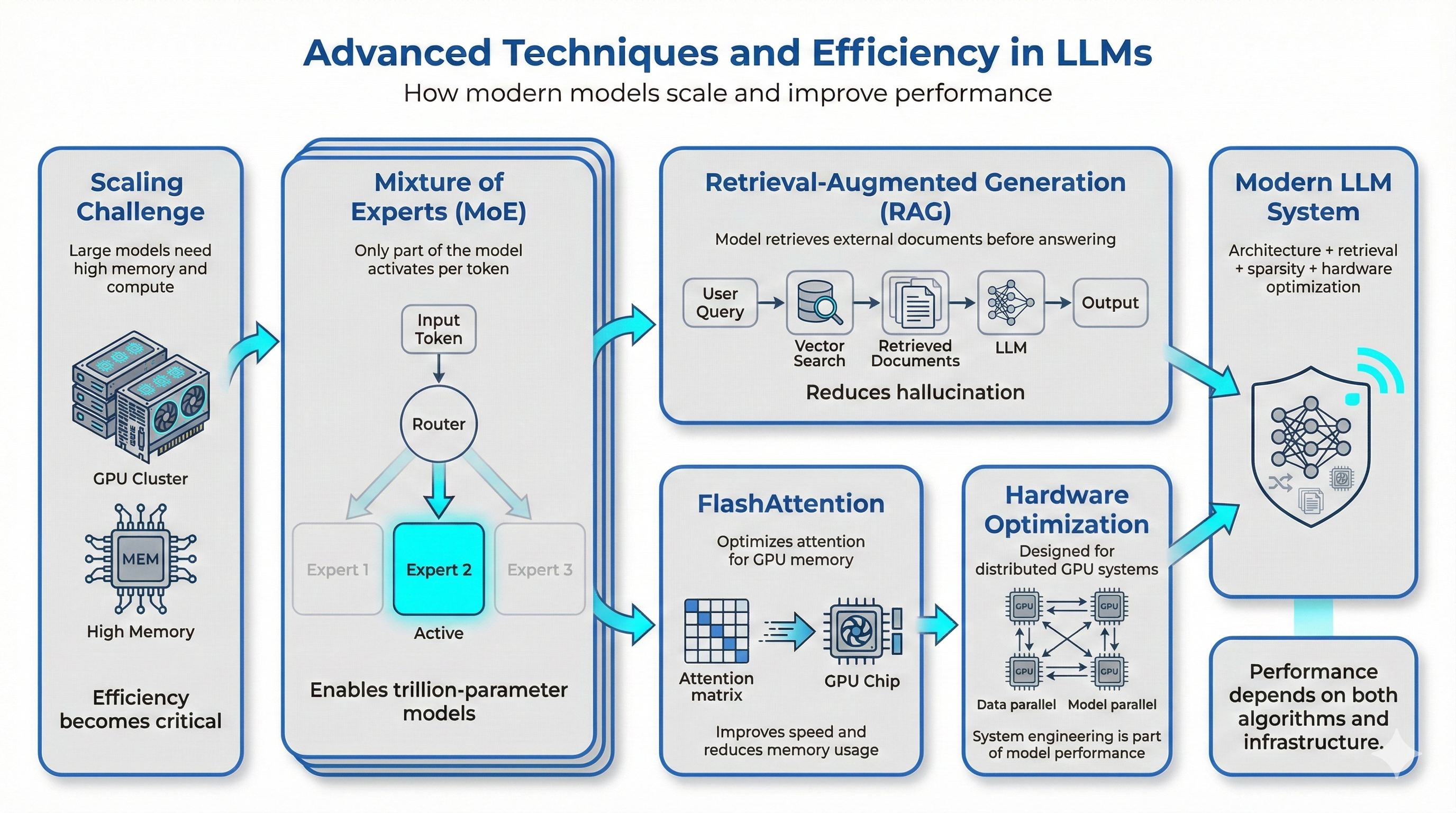

5. Advanced Techniques and Efficiency

Beyond architecture, training, and alignment, modern LLMs rely on several techniques to scale and run efficiently.

Figure: How modern models scale and improve performance (MoE, RAG, FlashAttention, hardware optimization).

How it works in simple terms. The diagram above shows how scaling challenges are addressed by combining several techniques:

- Scaling challenge. Large models need a lot of memory and compute (many GPUs and chips). So efficiency becomes very important: we need ways to make models faster and cheaper to run [8][10].

- Mixture of Experts (MoE). Instead of using the whole model for every token, only part of the model is active per token. A router sends each input token to a few experts (sub-networks); for example, only “Expert 2” might be active for one token. This is sparse computation: it allows models with trillions of parameters while keeping the cost per token manageable [8].

- Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG). The model can retrieve external documents before answering. The user query is turned into a vector; a vector search finds relevant documents; then the LLM generates an answer using both the query and those documents. This reduces hallucination and lets the system use up-to-date knowledge without retraining [9].

- FlashAttention. The attention mechanism uses a lot of GPU memory and compute. FlashAttention and similar methods optimize how attention runs on the GPU. They improve speed and reduce memory use, so larger models or longer sequences can run on the same hardware [10].

- Hardware optimization. Modern systems are built for distributed GPU setups: many chips work in parallel. Data parallel and model parallel ways of splitting the work are used. So system and hardware engineering are part of model performance, not only the algorithm [10].

- Modern LLM system. Together, architecture (e.g. MoE), retrieval (RAG), sparsity, and hardware optimization form a modern LLM system. Performance depends on both algorithms and infrastructure [8][9][10].

Mixture-of-Experts (MoE). In models such as Switch Transformers, only a subset of parameters is used per token [8]. This is called sparse computation. Models can scale to trillions of parameters while keeping computation per token manageable. The trade-off is more complex systems and the need for good load balancing.

RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation). RAG combines a retrieval system with a language model to improve factual grounding [9]. The model retrieves relevant documents and conditions its generation on them. This can reduce hallucination and allow knowledge updates without retraining. It also introduces new risks, such as prompt injection and manipulation of retrieved data.

FlashAttention and kernel optimization. Attention is very demanding in memory and compute. FlashAttention-2 and similar methods optimize attention for modern hardware [10]. For example, implementations on NVIDIA Hopper use CUDA kernel fusion and hardware-aware optimization to get large speedups. Scaling LLMs is therefore not only an algorithmic challenge but also a systems and hardware engineering problem [10].

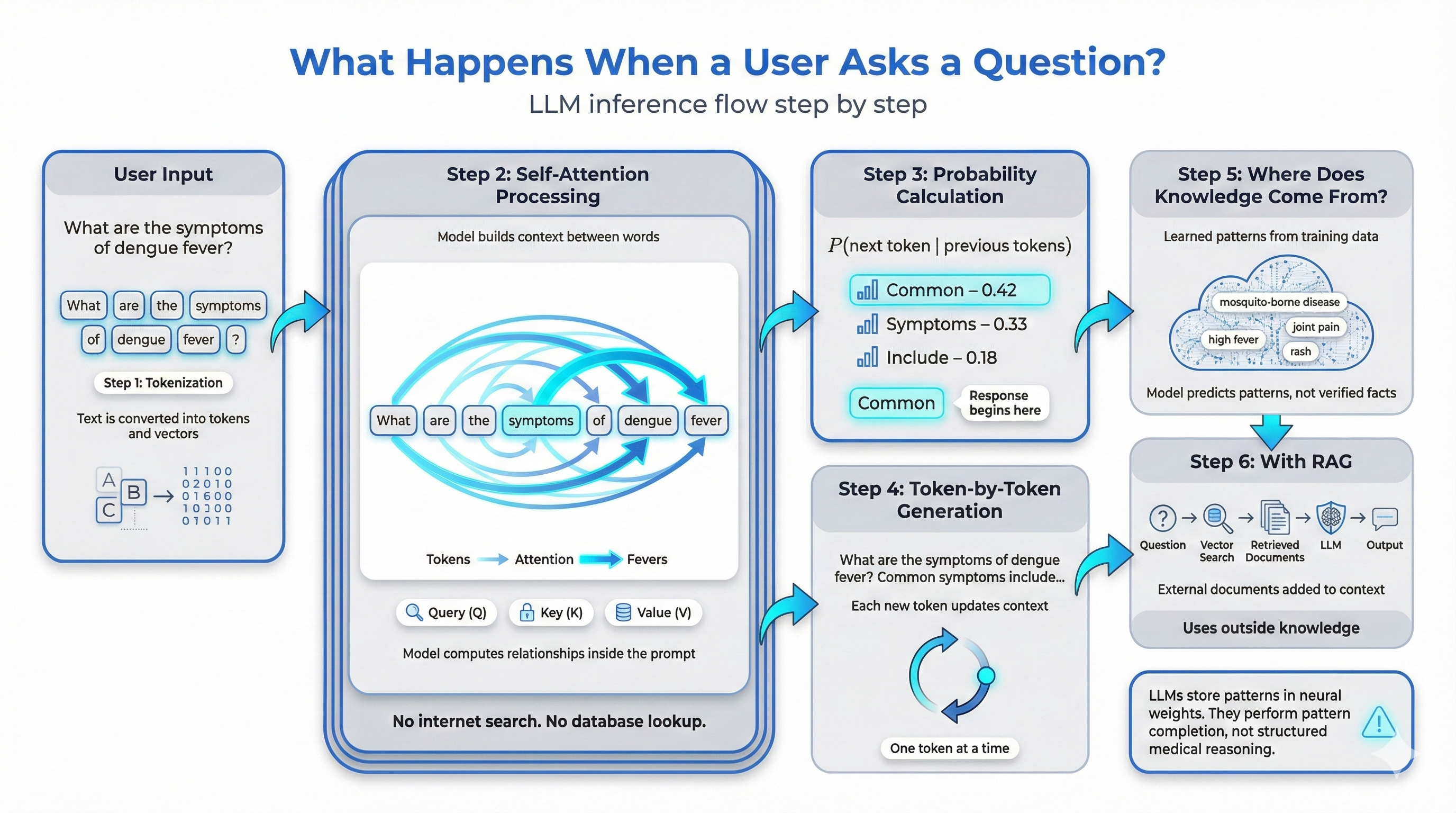

6. What Happens When a User Asks a Question?

Putting everything together: what matters in practice is what happens at inference time, when a user sends a question. Take for example: “What are the symptoms of dengue fever?” The diagram below shows the path from that question to the answer; the paragraphs that follow explain each step in one coherent flow.

Figure: LLM inference flow step by step (tokenization, self-attention, next-token prediction, generation, knowledge source, RAG).

Step 1: Tokenization. The question is turned into tokens (e.g. [What] [are] [the] [symptoms] [of] [dengue] [fever] [?]) and then into embedding vectors. At this stage the model does not search the internet or any database; it only converts text into numbers the network can process [1].

Step 2: Self-attention and context. The embeddings go through the Transformer layers. In each layer, self-attention uses Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V) to compute how tokens relate (e.g. “symptoms” to “dengue” and “fever”) and builds a single contextual representation of the question. That representation is a high-dimensional vector that encodes the meaning of the whole prompt. The model is not retrieving a stored paragraph; it is preparing to compute a probability distribution over possible next tokens [1].

Step 3: Next-token prediction. The model predicts the most likely next token. It computes:

P(next token | previous tokens)

It may assign high probability to tokens such as [Common], [Symptoms], [Include], and then picks one according to its sampling strategy. The response starts here [1].

Step 4: Token-by-token generation. After the first token is generated, the process repeats: each new token is added to the context (e.g. “What are the symptoms of dengue fever? Common symptoms include…”), the model updates the context, recomputes attention, and predicts the next token again. This continues until a stop condition. The model never produces the full answer in one go; it generates one token at a time [1].

Step 5: Where does the information come from? The model does not “look up” dengue fever in a database. The knowledge comes from patterns learned during pre-training [3]. If the training data included medical texts and web content about dengue, the model learned statistical links between “dengue fever,” “mosquito-borne disease,” “high fever,” “joint pain,” “rash,” and similar phrases. At inference it recombines these patterns. It does not check facts or guarantee correctness; it predicts what is statistically likely to follow.

Step 6: What changes with RAG? If the system uses RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) [9], the flow changes. Before generation, the question is turned into an embedding, a vector search is run, and relevant documents (e.g. medical) are retrieved and added to the prompt. The model then generates text conditioned on both the question and those documents, so the system can use external knowledge. Without RAG, the model relies only on what was learned in training.

Important clarification. An LLM does not store structured medical knowledge like a database. It stores distributed representations in its weights. When it answers about a disease, it is activating learned patterns across billions of parameters. This is pattern completion, not structured reasoning or medical diagnosis. That distinction matters for safety, hallucination, and reliability.

Final Consideration

An LLM (Large Language Model) is a probabilistic system trained to predict tokens. Its capabilities come from:

- The Transformer architecture [1]

- Massive scale (parameters, data, compute) and scaling laws [4], [5]

- Alignment (SFT, RLHF, RLAIF) [6], [7]

- Efficiency techniques (MoE, RAG, FlashAttention) [8], [9], [10]

It does not have symbolic reasoning, persistent memory across sessions, or guaranteed correctness. Its behavior is statistical and learned from data.

References

[1] Vaswani, A., et al. (2017). Attention Is All You Need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 30).

[2] Reflections. (2024, June 10). Mathematical details behind self-attention.

[3] Brown, T. B., et al. (2020). Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. NeurIPS 33, 1877–1901.

[4] Kaplan, J., et al. (2020). Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models. arXiv:2001.08361.

[5] Muennighoff, N., et al. (2025). Scaling Data-Constrained Language Models. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 26, 1–66.

[6] Ouyang, L., et al. (2022). Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. NeurIPS 36.

[7] Bai, Y., et al. (2022). Constitutional AI: Harmlessness from AI Feedback. arXiv preprint.

[8] Fedus, W., Zoph, B., & Shazeer, N. (2022). Switch Transformers: Scaling to Trillion Parameter Models with Simple and Efficient Sparsity. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 23.

[9] Lewis, P., et al. (2020). Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks. NeurIPS 33.

[10] Bikshandi, G., & Shah, J. (2023). A Case Study in CUDA Kernel Fusion: Implementing FlashAttention-2 on NVIDIA Hopper Architecture using the CUTLASS Library. Colfax Research.